1000 Cranes

The email from Debbie came out of the blue, a voice from the past.

Twenty years before, Debbie and Matt had studied with the same voice teacher at Trinity University in San Antonio, and had become best friends during weekly studio classes and diction lessons. On holidays, they shared rides home to the Midwest, swapping life stories fueled by the stash of candy they both consumed obsessively. Matt had sung at Debbie’s wedding in St. Louis in December 1991, the same December I transferred from Trinity University to the University of Missouri in Columbia, my hometown. While Matt and I had struck up a friendship in the music department at Trinity during the years we were students together there, I didn’t know Debbie back then. I was nineteen years old, and no friend of mine had gotten married, or even engaged. At that time, the idea of commitment to anything—a person, a passion, a life’s work or practice—seemed both attractive and incomprehensible at the same time.

The week before the ceremony, realizing he’d be driving right through Columbia, Matt called and invited me to lunch. Stopping by the house to pick me up, he met my parents and my grandmother, who was visiting for the holidays. We ate Chinese food at a small downtown restaurant.

After lunch, Matt and I hugged and said goodbye. At the time, I had no reason to assume that our relationship would continue. He was simply checking up on me, I thought. That was the sort of thing Matt did, he checked up on his friends. And that’s what we were: good friends, nothing more.

But the night after the wedding, Matt called. He was buoyant, chatty. He wanted to come visit again on his way back to Kansas City and could be there in time for breakfast on Sunday morning. I made waffles. Neither one of us drank coffee back then. We ate and talked. That was it. The earth did not shake or even rattle in the slightest.

Matt left. I spent the rest of the day practicing the piano.

When the email from Debbie arrived, in March of 2010, it was hard to believe that twenty years had passed since Matt sang at her wedding. I retained only a fuzzy memory of hugging Debbie as she and Dave went through the receiving line at our wedding. “Hang in there,” she told me. “The end is in sight.” After living for some time in New York City, Debbie and Dave had moved from their Upper West Side apartment to a yellow farmhouse of the outskirts of Kansas City. Once on a trip home we visited them. They had chickens and a toddler. Debbie made cookies.

It had been at least a decade since Matt and Debbie had been in touch. In her email, Debbie made a passing mention of Dave and their two children. She was working on a graduate degree in music therapy. Her message was chatty, upbeat, the kind of friendship reconnect after many years that happens these days thanks to social media tools like the internet and Facebook. Matt replied quickly, summarizing the past years in a few sentences: "I am still married to my first wife and still conduct choirs. Amy teaches piano lessons and performs regularly. We've been in Albuquerque almost seven years now. Most days, we like it."

Debbie wrote back the next day, the façade of forced cheerfulness gone, "My news is sad. During routine (it's always ‘routine,’ isn't it?) gall bladder surgery, it was discovered that I have stage four pancreatic cancer."

Debbie’s diagnosis of terminal cancer hit me hard, far out of proportion for the relationship and history she and I shared. I could not stop crying. I sobbed in the shower, wept while swimming my morning laps, sat through my mediation practice with tears rolling down my face. The smallest thing would set me off: Matt offering to bring me a glass of wine while I took a bath; the sight of the first tulip that spring; a tiny lollipop of a student squealing, “Miss Amy! Guess what I got for my birthday!” I couldn’t remember ever crying so much. There was no bottom to my sadness, an undefinable internal ache finding tangible form. For her, I cried.

Three months after receiving Debbie’s email, my bike was hit by a car (“Were you on it?” asked one alarmed student when she heard the news.). My right leg was fractured like a vase. The bone held together, but the MRI revealed hundreds of cracks in the tibia plateau, the place where the shinbone enters the knee joint. I spent the summer performing and teaching on crutches. The accident, my own small brush with mortality, rattled my already fragile core, exacerbating the sense that life was rushing by me out of control. In the early morning hours, I would wake up, reliving the accident: seeing the moment just before the impact, feeling myself hitting the ground, my leg twisted beneath me. It wasn’t hard to imagine that this incident could have ended very differently. A slight shift and I could have lost my life, or—every pianist's nightmare—the use of my hands.

It might have been only a broken leg, but with my newly limited mobility, even my most everyday routines—the all too familiar harmonic progression I had been circling through for years—were compromised. Ironically, the very mundane things I often resented, slamming myself up against their predictable walls, were now all I wanted. I could no longer get my own glass of water before bed; I couldn’t manage the basement stairs in order to do laundry or feed the cats; my garden went untended. All my normal practices of cycling, yoga and walking were suspended. I felt trapped inside the house, depressed and angry, the circumference of my world growing smaller and smaller, the box shrinking around me. Knowing I was the comical figure of my own Greek tragedy did not make me any less hysterical. I was ready to trade my whole bucket list—the mountains I wanted to climb, the music I wanted to play, the places I wanted to visit—to have my life back, preciously intact.

Periodically, we'd get updates from Debbie. “My dad installed a hand sanitizer dispenser outside the front door,” she emailed. “That’s his response to ‘My daughter has terminal cancer.’ Let’s make sure everyone has clean hands.” Every time we heard from her, I felt guilty for complaining about my bad leg, my small temporary handicap. While they had chosen to treat the cancer aggressively, there was no sign the chemotherapy was working, or buying her any time. The tumors were everywhere: in her pancreas, her stomach, her diaphragm. "What do I need a diaphragm for anyway," she wrote, "except to sing those high C's?" Each update from her was a stab in the gut, a painful reminder that regardless of the bargains I had been carelessly making with the devil, I probably didn’t have to trade my bucket list for a normal future. Impatient as I was, the time would eventually come when I would be completely healed, and she wouldn’t. The sand in the hourglass was quickly falling, numbering her days, piling up the dreams that she would never own. She wouldn’t be able to walk her dog, tend her garden, sing those soaring high notes. She would miss holidays and birthdays and anniversaries. She wouldn’t watch her children grow up.

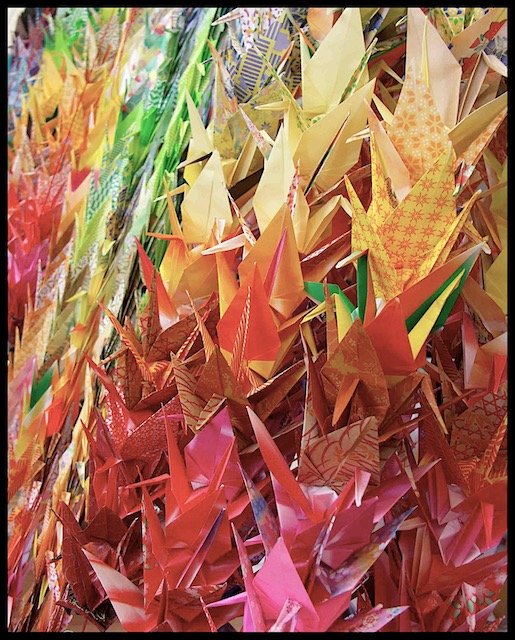

About seven weeks after the accident, on the eve of my birthday, a friend walked through our front door carrying two bunches of garlands. On them were strung 1000 paper cranes. A thousand birds. According to the ancient Japanese legend, the person who folds 1000 cranes is granted a wish. The recipient of the gift of 1000 cranes receives good luck, health and prosperity. "I thought you needed some luck," Jerome told me.

We hung the cranes over my desk. Even disguised as a birthday present, they were an outrageous gift, really, in the face of a broken leg. Everyone commented upon them. “Ooooo…Miss Amy! What are these?” my students asked, their eyes wide. “Does your friend have a lot of time?” several kids wondered out loud.

One night Matt said, "I want us to fold cranes for Debbie.” That weekend we invited friends over for a crane-folding party with cocktails and appetizers. Writing and working at my desk as the summer rolled into fall, I felt blessed by the presence of the colorful flock of paper birds, the reminder they provided that life was fragile and that even the small, seemingly senseless act of folding cranes could be a powerful symbol, a prayer offered to help heal a broken world. Between piano lessons, I taught my students to fold cranes and together we made cranes during monthly performance classes. Some children learned quickly, their tiny fingers easily adapting to the fine motor coordination and attention to detail needed to successfully fold a crane from beginning to end. Others were impatient, as clumsy with the colored paper as they were with their scales. Slowly, the pile of cranes in the corner of the studio grew: five hundred, six fifty, eight ninety-nine. "Who are these cranes going to?" the kids asked, as if wondering who was worthy enough. "Too bad Beethoven isn't alive."

New Mexico was an item on Debbie’s bucket list. She and Dave began planning a trip after her next horrendous round of chemotherapy, the dates chosen to coincide with a Quintessence concert Matt was conducting in mid-October.

The Tuesday night before the concert, Debbie and Dave came to dinner. "You look exactly the same," she said to me as she got out of the car. "After a dozen years, how is that possible?"

She didn't look the same. The cancer and subsequent treatments had aged her decades. When I hugged her, she was skeletal, transparent almost. They had tried everything, Debbie told us, to no avail. Just that afternoon they had gotten word that she had not been accepted into a trial at MD Anderson.

But aside from the tangible, visible evidence of the cancer in front of us, that night could have been any evening among old friends, the many years and distance between us dropping away completely. Debbie noticed everything: she admired the bold colored walls and the New Yorker covers hanging in the sunroom, picked up books from the shelves, studied the framed photos sitting on a corner table. She crouched down to pet the cats who were playing hard to get. “You are going to make me work for this, aren’t you?” Debbie said to Godiva, as she knelt on the floor. Looking around at the yellow and red living room and the purple walls of the dining room, she said, "I’ve always wanted to paint my living room teal. Amy, tell Dave that teal works just fine with red."

While Matt made dinner, Debbie and I fell into a broad sweeping conversation, circling over the last two decades. We reminisced about a trip to New York that Matt and I had made before we were married when we slept on the floor of their apartment and spent days tramping across the city through the snow. Debbie had happily traded her off-Broadway performing career for two kids, a Midwestern farm with chickens and cows, and a job teaching music to preschool children. “No regrets,” she said. She listened quietly while I talked about my work: the variations of teaching, performing and practicing that gave my days and hours shape and form. Thinking about all the sacrifices and heartache that every path taken or not thrusts upon us, I fell silent. I have spent my life practicing.

Almost under her breath Debbie asked, “Amy, is there any other way you’d rather spend your time?”

The question hung in the air. Is there any other way you’d rather spend your time? She sat smiling at me, unblinking, unaware that she had just put my undefined ache into stark relief. After all, she was already on borrowed time, and it was quickly running out. Is there any other way you’d rather spend your time? All at once, something within me shifted, the pattern behind the variations suddenly obvious, a previously blurry lens finally clicking into place. I looked at her, unformed words caught in my throat.

Two days later we got a phone call from Dave. They were at the airport. Debbie had deteriorated to the point that they were heading home.

The 1000 origami cranes that we had intended to present to Debbie after the concert were flattened, coiled and shipped to Kansas City. Back home, Debbie failed rapidly, and a week later went into hospice care. Tuesday morning, three weeks to the day after our dinner together, we got word that she had died.

It has been thirteen years since Debbie’s death, but lately she’s been on my mind. Last weekend Quintessence performed a piece called The Sacred Veil by the American composer Eric Whitacre. The text was written by poet Anthony Silvestri, who lost his young wife to ovarian cancer in 2005. The text was his response to that loss and his journey of grief and recovery. This piece is not for the faint-of-heart, and it came with a lot of emotional challenges for both the musicians performing the work and the audience listening to it. But it is a work that gives voice to our basic humanity, our capacity for love, and our ability to find hope and beauty in the face of great sadness.

Getting into the trenches with such music and texts would make anyone ponder death, for sure. But in case I wasn’t paying attention, there has been other sobering moments to wrestle with in the last few months as well. While we were in rehearsals for The Sacred Veil, my aunt died of cancer six weeks after her initial diagnosis. A favorite professor from graduate school died the week of the performance, also of cancer. My parents have had a number of unexpected health challenges, big and small, including a round of Covid for each of them. Nothing is permanent, I know, but the very fleeting nature of life, the sacred veil between this world and the next, has seemed particularly fragile lately.

In October of 2010, Matt and I flew to Kansas City for Debbie’s funeral. At the church, we greeted Dave. "Hey," he called out, catching sight of us in the receiving line, "there are a thousand cranes in my house." We laughed, or choked, the two at that point being almost one. During the service, a letter Dave had written was read to the grieving congregation, "There is a long list of things Debbie will never do, and almost as long a list that I will never do with her. If I have any advice to offer today it would be this: Don't wait."

The next day we stopped by their yellow farmhouse to say goodbye. Dave told us about their abbreviated time in New Mexico after we had seen them. The morning after our dinner together, they had gone on a hot-air balloon ride. The balloon had veered off-course and drifted for several hours before landing in someone’s chicken coop. He laughed, “The owners were nonplussed, as if this kind of thing happened every day. You do start to understand why this might be the state that embraces the whole concept of UFOs.” After their balloon adventure, they went to Santa Fe, intending to spend a couple of days. Debbie had taken one walk around the Plaza before collapsing, her internal organs beginning to shut down, one by one. Talking to Dave, I realized with a start that the last good, relatively normal, night the two of them had together must have been our shared dinner. The irony: that her wedding would always be linked to the beginning of our story while we would forever be married to the end of hers.

The three of us sat and talked for an hour. Lying on the desk in the corner was a purse, the zipper opened to reveal its contents: a tube of lipstick, a wallet stuffed with receipts, a handful of paint swatches. Debbie's purse.

Don't wait, I caught myself thinking, remembering Dave's words read the day before. As we talked, I looked over at Matt. He caught my eye. You okay? he mouthed at me. Over Matt’s shoulder, I could see the cranes (a thousand cranes!) in the other room, hanging over Debbie’s empty hospice bed. I nodded.

Is there any other way you'd rather spend your time? Debbie had asked me. For weeks, her question had lingered in the air, haunting me, demanding a response. Ten thousand times a day, we make tiny, seemingly inconsequential, decisions—this or that? a canon or a toccata or a sarabande?—and on such small choices a life is created. I have spent my life practicing. Is there any other way you’d rather spend your time? No, I thought. No.

Yesterday, Matt and I celebrated 31 years of our love story, March 18 being the date of our first kiss. I take nothing for granted these days, knowing how many of our paths taken and choices made are so random and unassuming. How simple it would have been for Matt to have driven right by and not stopped when he was traveling to Debbie’s wedding so many years ago. We could have so easily slipped into other lives, other roles, and been none the wiser. The very particulars of our world are precious, and fragile, and fleeting indeed.

Somewhere, someone goes to the piano and begins to practice scales. Someone begins to write a fugue. Someone sits down and starts to follow her breath. Someone counts laps in a pool. Someone begins his daily sun salutations. Someone turns over a piece of paper and folds a crane. The meaning is in the doing.

Somewhere, a bird stops roaming and flies home.