A World of Distractions

Lately I have been thinking a lot about my grandparents. Specifically, the events of the last few weeks—the shooting in the Pittsburgh synagogue, the bombs mailed to critics of the Trump administration, the elections on Tuesday—make me think of a letter my grandfather sent my grandmother some seventy-five years ago.

Tonganoxie, Kansas

Jan. 4, 1942

Dear Gracie:

…I feel a little guilty that you weren’t better entertained on your New Year’s vacation after taking the time and expense of a trip up here, but we’re quite simple people and that is about the usual extent of our celebrations anyway. It seems to me a lot of other people are going to be forced to live a more simple life during the next few years and maybe we people who are used to a simple form of life won’t be hurt so badly as the ones who are used to more hilarity and excitement…

I surely enjoyed your visit here last week and hope you’ll come again.

Love, Kenneth

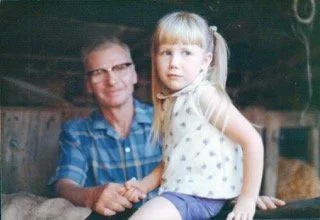

At the time he wrote this, my grandparents have known each other for three months. Kenneth has maintained a steady written correspondence, reporting about safe trips homes after visits, chatting about neighbors and friends, sending Grace greetings from his sisters.

But this letter is the first mention of the war. There was no reference to Pearl Harbor after the attack on December 7th. He expressed no written thoughts or concern about the country entering the conflict or about friends or acquaintances who might be enlisting. Only this vague passing mention about the value of living simply.

Of course, Grandpa was a Kansas farmer living in the literal heart of the United States. The war in Europe and the Pacific must have seemed somewhat incomprehensible, a world removed from his daily routines of chores and responsibilities.

Or perhaps what appears to be ignorance or isolation really demonstrates a deep manifestation of the discipline of practice as a way of life. Most people, even when faced with unspeakable disasters, deaths and diseases, simply keep going, their daily habits and practices sustaining them. They feed their children and go to work and coach soccer and teach Sunday school. I am reminded of a friend who told me that on the evening of 9/11, she went to a yoga class and the teacher leading the students through their series of poses never once mentioned the horrific events of that morning. At the time, she was angry and felt like he was ignoring reality. Later, however, she reconsidered this assessment, and wondered if his reaction wasn’t the right one: that as people of practice, whatever that might be—milking cows, plowing fields, doing yoga—our job is to keep practicing, even in the face of difficulty.

Another friend who was on retreat at a Catholic college and seminary when Trump was elected in 2016 told me that the evening after the election she went to mass with the resident monks. She found great solace that night in the fact that these monks were doing what they did every day—working, praying, singing—and that no matter who might be elected, no matter what might happen in the world, they would continue to work and to pray and to sing.

I find myself thinking about this as I read the letter written by my grandfather during one of the worst wars in recent history. There is still plenty to distract us if we want to be distracted from our work and practices; the world today groans with its own heartaches, wars and bigotry. There is plenty of compelling late-breaking news cycles to watch, plenty of horrific stories to get caught up in, plenty of both real and manufactured dramas to grab our attention.

We are constantly told that the world we live in is “unprecedented,” but I wonder about that. There have always been distractions, good and bad: earthquakes and tsunamis, the Black Plague and the Crusades, love affairs and babies, new jobs and clogged toilets, birthdays and anniversaries. It reminds me of the student who once said (and quite excitedly I must add), “Miss Amy! I couldn’t practice the piano this whole week because I lost a tooth!”

And yet, in spite of it all—in spite of who is in control of Congress, in spite of the new ways we find to hate one another, in spite of the divisions of all kinds among us—people continue to plant tomatoes and hold downward-dog for five slow breaths. We prepare dinner every night and give out Halloween candy to tiny ghosts and goblins knocking at our door. We teach piano lessons and learn Bach inventions. We pray and sing, cry and laugh, bake pies and roast turkeys.

In The Pastor as Minor Poet, Craig Barnes writes, “After wasting far too many years trying to do the spectacular, it has finally occurred to me that God loves routine. All of creation holds together by the same things happening again and again, whether those are great things, like planets revolving around stars, or very small things, like electrons going around and around their nucleus. And with each rotation, year after year, through winter, spring, summer, and fall, if you are paying attention, you can almost hear the doxology: ‘Praise God, from whom all blessings flow.’ Similarly, we are not asked to be other than a part of this created order who get up, go to work, care for children, make meals, do laundry, pay bills, and go to bed, only to rise the next morning to do it all again. ‘Keep on doing . . .,’ the apostle commends. But along the way, those whose pastors have taught them to pay attention do it all as doxology.”

The world keeps spinning. Keep practicing.