The Sacred Pause Button

We all have our sacred places in this world; Georgia O’Keeffe’s house in Abiquiu is one of mine. Situated on a hill overlooking the northern New Mexico landscape, it is a rambling hacienda-style house with an inner courtyard and several independent wings, housing living quarters and bedrooms and a long studio with a wall of windows. For anyone familiar with O’Keeffe’s work, the view from the studio is immediately recognizable. There is the mountain she painted over and over again. There is the road leading back to Española. There are the mesas and the hills and the cottonwood trees that she turned to for inspiration again and again.

O’Keeffe restored this property in the 1940s, and it became her primary residence after the death of her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, in 1946. After her death in 1986, the house and garden were turned into a museum, which one can tour with a reservation. I’ve done so twice and would happily make it an annual pilgrimage. Everything about this monument to a single independent woman artist speaks to me: the jars of herbs and tea leaves on shelves in the kitchen, the huge jade plant that still grows in the corner of her living room, the walled garden with hollyhocks and fruit trees. This is the essence of a well-edited life, whittled down to the basics of form and function and purpose. On my bookshelf is an art book about O’Keeffe entitled The Poetry of Things, and that describes exactly the environment she created in Abiquiu: pure poetry. I want her spare, strong aesthetic. I want to live fully inside a life of practice and beauty and meaning. I have never aspired to be a painter, but I want to be Georgia O’Keeffe when I grow up.

Last spring a couple of girlfriends and I toured the house at Abiquiu. On the way, we stopped at the Georgia O’Keeffe museum in Santa Fe, a beautiful and small art museum just off the plaza. In addition to a rotating collection of her art, there is a film about O’Keeffe’s life that plays continuously inside the entrance of the museum. Although I have seen the film many times before, last March something new hit me. The narrator was describing the period right after Stieglitz’s death and mentioned, almost in passing, that for several years O’Keeffe was dealing with Stieglitz’s papers and painted almost nothing.

. . . for several years O’Keeffe . . . painted almost nothing.

I didn’t realize I had been holding my breath, but something in me exhaled when I heard that seemingly insignificant statement. Suddenly I felt like I had been given permission, a license to stop my endless scurrying and to put a graceful pause button on my relentless productivity. For several years, O’Keeffe painted almost nothing.

As a culture, we are endlessly caught up in our to-do lists, the proof of our accomplishments, the drive to make something of our lives. We are easily discouraged by weeks and months and years where we are distracted by papers or children or illness or other preoccupations. We rail against any interruption to our plans, our art, our life’s work and purpose.

For several years, O’Keeffe painted almost nothing.

Since returning home from Europe a month ago, I have found myself thinking a lot about O’Keeffe’s pause button as I have scampered to put the pieces of my life and practices back into place. It is all too tempting to try to work faster and harder in a frenzied attempt to make up for the “lost” month of travel, forgetting that in a long creative life that a single month is an almost trivial aside in the larger, more generous view. “Each year I resolve to believe there will be possibilities,” the playwright Wendy Wasserstein wrote. “Every year I resolve to be a little less the me I know and leave a little room for the me I could be. Every year I make a note not to feel left behind by my friends and family who have managed to change far more than I.”

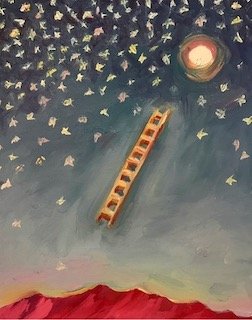

Last fall I asked a young artist and former piano student to design our November studio recital program cover. A week before the recital she sent a jpeg of a painting she had done. It is a gorgeous depiction of a night sky over a red mountain range. Hanging in the sky is a ladder, a stairway to the moon. “It’s very Georgia O’Keeffe inspired,” Maggie told me.

Two months into this new year (and a year with an extra day in it to boot!), it is too easy to be discouraged by the intentions forgotten, the resolves abandoned, the possibilities already undermined. To view a week or a month sorting taxes or tending to a sick child or clearing out leaves from the garden as wasted time, an insult to our real life and work. For several years, O’Keeffe painted almost nothing. This was the same woman who famously said, “The days you work are the best days.” There must have been some tension and frustration in those years of “almost nothing.” Somehow this comforts me.

Maggie’s painting now hangs in the corner of the living room where I can see it from the piano bench. Two hours north of my little corner of the universe is a house full of light where Georgia O’Keeffe once lived, evidence of a life gracefully negotiated and intentionally focused, a reminder that unwelcomed interruptions are not dead ends, but rather that pause buttons can be holy and sacred. Last weekend, I hung up photographs from our recent European travels: a photo of the fog enveloping St. Stephen’s steeple in Vienna, the moon suspended over the Great Synagogue in Budapest, the sun setting behind the Basilica di Santa Maria in Venice. Touchstones of a pause button. A ladder of possibilities.

Almost nothing.